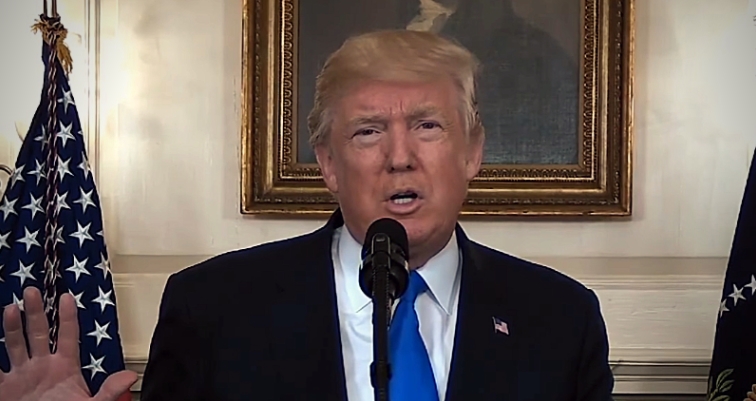

The media vs. Donald Trump: why the press feels so free to criticize the Republican nominee

08/16/2016 / By trumpnews

There is a case to be made that the media created Donald Trump. It was, reportedly, his anger at being dismissed by political pundits that led him to run for president in the first place. And it was, arguably, the media’s wall-to-wall coverage of his every utterance that powered his victory in the Republican primary.

(Article by Ezra Klein)

But slowly, surely, the media has turned on Trump. He still gets wall-to-wall coverage, but that coverage is overwhelmingly negative. Increasingly, the press doesn’t even pretend to treat Trump like a normal candidate: CNN’s chyrons fact-check him in real time; the Washington Post reacted to being banned from Trump with a shrug; BuzzFeed Newspublished a memo telling reporters it was fine to call Trump “a mendacious racist” on social media; the New York Times published a viral video in which they simply quoted the most vile statements they heard from Trump’s supporters.

This is not normal. There are rules within traditional political reporting operations about how you cover presidential candidates. If Marco Rubio had won the Republican nomination, he might have lied in some speeches, but CNN’s chyrons would have stayed dull. If Ted Cruz had been the GOP’s standard-bearer, he, like Trump, would have kooks at his rallies, but it would be seen as a cheap shot for the New York Times to record the worst of their vitriol and send it ricocheting across Facebook. If Jeb Bush had banned the Washington Post from covering his campaign over charges of bias, the paper would treat it as an existential threat.

It’s a common criticism of political reporting that it’s hampered by a faux-evenhandedness — if one side says the sky is blue, and the other side says it’s orange, then the headline will be “Opinions on Color of Sky Differ.” But that hasn’t happened this year. The media has felt increasingly free to cover Trump as an alien, dangerous, and dishonest phenomenon. “Trump has freed journalists from the handcuffs of false equivalence,” says Brian Stelter, host of CNN’s Reliable Sources.

Trump, for one, has noticed the negativity of his coverage. It’s become a favored explanation for his sagging poll numbers:

If the disgusting and corrupt media covered me honestly and didn’t put false meaning into the words I say, I would be beating Hillary by 20%

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) 14 de agosto de 2016

Like with much Trump says, there’s a kernel of a point here. While it’s ridiculous to suggest the media likes Hillary Clinton — her relationship with the press is famously, legendarily toxic — the media is increasingly biased against Trump. He really is getting different, harsher treatment than any candidate in memory. That he deserves it is important context to the discussion, but not, I think, the whole explanation.

Trump’s deteriorating relationship with the press is revealing about Trump himself — about the ways in which an attention-at-all-costs strategy that carried him through the primary has proven maladaptive in the general election. But it’s also interesting as a window into how the political press works, and why it does or doesn’t follow rules of evenhandedness in different circumstances.

After watching the media’s comfort calling out Trump grow in recent months and speaking to reporters, editors, and media critics about why, I think there are four main reasons a different set of rules have emerged for covering Trump.

Both sides do it (where “it” = bash Trump)

There is an idealistic and a cynical reason for automatic equivalence in political reporting. The idealistic reason is that the press isn’t supposed to take a side because the audience needs the news delivered by institutions that will always, no matter what, deliver both sides — and who is the press to choose which side is right, anyway? The cynical reason is that members of the political press need to report amongst elites from both political parties, and equivalence-based reporting ensures that you don’t lose too much access on either side, and that’s the real game — making sure both parties are willing to talk to you, and members of both parties will subscribe to you. Both are true.

But Trump short-circuits all that. You can criticize Trump sharply and be applauded, both publicly and privately, by senior Republican figures. The most despairing, hysterical commentary I’ve heard about Trump this cycle has been from Republicans speaking off the record — including Republicans who have endorsed Trump! In this way, the “evenhanded” view of Trump that emerges from traditional reporting is that he’s a dangerous maniac — Democrats say it, and so too do many top Republicans.

A quick story. Back during the primaries, I published a piece — and recorded a video — calling Donald Trump’s rise a terrifying moment in American politics. The analysis was unsparing.

“Trump is the most dangerous major candidate for president in memory,” I wrote. “He pairs terrible ideas with an alarming temperament; he’s a racist, a sexist, and a demagogue, but he’s also a narcissist, a bully, and a dilettante. He lies so constantly and so fluently that it’s hard to know if he even realizes he’s lying.”

After the piece published, I got a call from a very conservative Republican member of Congress. He wanted to talk about the article, his office said. I figured he’d be angry. Instead, he congratulated me for speaking out.

That member of Congress, by the way, has now endorsed Trump.

I think this is why the Washington Post, for instance, isn’t panicking over being banned from Trump’s events. If the Post believed the Republican Party had turned on it so sharply that they were now permanently blacklisted from doing even basic reporting on GOP campaigns, it would be an institutional crisis.

But the Post doesn’t believe that’s what Trump’s reaction represents, because Trump doesn’t speak for the Republican Party. Plenty of Republicans are happy to see the excellent, critical coverage the paper has offered of Trump and are appalled by Trump’s petulant reaction. The Post’s long-term relationships on the right aren’t imperiled by their feud with the Trump campaign — they may even be being strengthened by it.

This is also a partial explanation for why coverage of Trump has become so much more negative since the primary. Back when Republican elites took Trump less seriously, and were often trying to use him as a tool to attack other leading Republicans or push their own agendas that they believed would respond to the grievances of Trump voters, there was actually less behind-the-scenes criticism of his temperament and campaign, at least in my experience. Then, top Republicans were, by turns, annoyed, bemused, and reflective when talking about Trump. Now they are disgusted, panicked, and desperate. That is manifesting in the coverage of reporters talking to those Republicans.

Trump’s conspiracy theories and lies offend the press in a visceral way

The strange alliance that has emerged between even Trump-supporting Republican elites and a critical press corps has been nurtured by Trump’s bizarre conspiracy theories and his baldfaced lies, which offend and unnerve both sides.

“The things Trump says are demonstrably false in a way that’s abnormal for politicians,” says the Atlantic’s James Fallows, who wrote the book Why Americans Hate the Media. “When he says he got a letter from the NFL on the debates and then the NFL says, ‘no, he didn’t,’ it emboldens the media to treat him in a different way.”

Top @NFL spokesman tells me: “While we’d obviously wish the debate commission could find another night, we did not send a letter to Trump.” — Brian Stelter (@brianstelter) 30 de julio de 2016

Politicians are not fully truthful. Everyone knows that. But they make a basic effort at being, as Stephen Colbert put it, truth-y. The statistics they cite as usually in the neighborhood of correct. The falsehoods they offer are crafted through the careful omission of fact rather than the inclusion of falsehood. They may say things journalists know are wrong — climate change denial is a constant among Republican officeholders — but they protect themselves by wrapping their arguments in well-constructed controversy or appealing to hand-selected experts. This is part of how political reporting operates. Politicians are allowed to be wrong, but they can’t lie. Trump just lies. “Whether Hillary Clinton was truthful about her emails is such a complicated and almost insidery story that it requires a multi-thousand word Politifact explanation,” says Stelter. “Donald Trump calling Obama the founder of ISIS can be fact checked in a chyron.” And indeed it was:  Reasonable people can and do disagree as to whether Trump’s comment should’ve been taken so literally. But that’s precisely the point: Trump’s tendency to spout wild, outlandish, easily disproven falsehoods and conspiracy theories has shredded any benefit of the doubt he ever got from the press. A politician who would repeatedly suggest that Ted Cruz’s father was involved in JFK’s assassination based on a grainy photograph in the National Enquirer is not a politician who is even attempting to abide by the norms of truth-y discourse. And if Trump isn’t going to even pretend to be vetting his sources and fact-checking his arguments, then the press isn’t going to pretend to believe what he’s saying.

Reasonable people can and do disagree as to whether Trump’s comment should’ve been taken so literally. But that’s precisely the point: Trump’s tendency to spout wild, outlandish, easily disproven falsehoods and conspiracy theories has shredded any benefit of the doubt he ever got from the press. A politician who would repeatedly suggest that Ted Cruz’s father was involved in JFK’s assassination based on a grainy photograph in the National Enquirer is not a politician who is even attempting to abide by the norms of truth-y discourse. And if Trump isn’t going to even pretend to be vetting his sources and fact-checking his arguments, then the press isn’t going to pretend to believe what he’s saying.

Press critic Jay Rosen has an interesting perspective on this. What Trump is doing, he says, is journalism-in-reverse. “The birth certificate is a good example,” he says. “When you take a fact verified as fully as it can be in journalism, like Obama was born in the United States, and you say it’s not true, it’s a lie, energy is released by that. You can use that energy to power a campaign. But that offends journalism because it reverses it. It takes something that’s been nailed down and introduces doubt about it to release controversy and chaos.” Trump flouts the epistemological basis of contemporary political discourse — his taste for conspiracy theories, his unwillingness to back off of clear falsehoods, and the seemingly effortless and needless nature of his lying (what purpose did saying he had received a letter from the NFL complaining about the debate schedule even serve?) have opened a yawning gap between the candidate and the people who cover him.

Yes, the press is biased — and in a way that’s particularly bad for Trump

In 2004, Daniel Okrent, the then-ombudsman of the New York Times, wrote a famous piece with the headline, “Is The New York Times Liberal?” The first words of the article? “Of course it is.” Okrent’s actual argument, as Rosen reminded me in our conversation, was more interesting, and more nuanced, than the headline. What Okrent really wrote was that the New York Times was staffed by New Yorkers, that it emerges from a “tumultuous, polyglot metropolitan environment,” and it reflects those values. The newsroom’s liberalism isn’t the economic liberalism of Ted Kennedy but the social liberalism of anyone who enjoys walking around Manhattan at night. It’s no accident that the sole issue Okrent examines at length in his column is gay marriage. I have worked in a number of newsrooms and I know writers and editors in many, many more. There’s no mainstream newsroom I know of that is uncompromising in its advocacy for single-payer health care, or that has launched a longtime crusade for more foreign aid. If anything, the press tilts towards deficit hawkery in its economics and a (deserved) skepticism of governmental competence and honesty in its instincts. But the national press is undoubtedly cosmopolitan in its outlook — it is based in New York and Washington and Los Angeles, and it prizes diversity, tolerance, pluralism. Within newsrooms, these ideas aren’t seen as political opinions, but as fundamental values. There is no “other side” worth reporting when it comes to racial equality, no argument that needs to be respected when it comes to religious intolerance or anti-LGBTQ bigotry. More than Trump’s campaign is conservative, it is anti-cosmopolitan. Trump’s comments on Mexicans, on Muslims; his reaction to the Khans and to Megyn Kelly; his jingoism and instinctual mistrust of immigrants; all of this amounts to an anti-cosmopolitan ideology that really does run Trump smack into a deep-seated bias in America’s urban newsrooms. This is the subtext for a smart column my colleague Matthew Yglesias wrote about the racial resentment powering support by Trump. Journalists want to be empathic and respectful toward Trump’s supporters even as they’re appalled by much of what Trump is saying, and by even more of what his supporters are saying. And so there is a tendency to recast straightforward concerns about immigration, Muslims, minorities, and declining white privilege as expressions of the much-more respectable, and easily addressable, class of concerns known as “economic anxiety.” It is easy for the press to sympathetically cover doubts about trade agreements and hard for them to sympathetically cover a ban on Muslim travel. But that has left the press in the odd position of trying to create a Trumpism it can cover respectfully even as it covers Trump brutally.

The press is afraid of Donald Trump

Finally, but not unimportantly, the press is afraid of Donald Trump in a way unique to any candidate I’ve covered. Members of the media think Trump a threat to the free press as an institution. Yglesias does a nice job rounding up the evidence:

Finally, but not unimportantly, the press is afraid of Donald Trump in a way unique to any candidate I’ve covered. Members of the media think Trump a threat to the free press as an institution. Yglesias does a nice job rounding up the evidence:

Throughout the campaign, Trump has indicated that as president, one of his top priorities will be to make it easier to stifle media criticism of himself: Trump has vowed to “open up the libel laws” to make it easier to deploy litigation and threats of litigation to silence criticism. He has also vowed to use the president’s regulatory authority to damage the business interests of investors in media companies that criticize him. He maintains a blacklist of reporters and media outlets prohibited from covering his events. His campaign manager allegedly assaulted a reporter covering a Trump event. Trump himself has incited crowds at his rallies against specific reporters. His recent anti-media tirades have, again, featured the suggestion that he’s not just complaining but would genuinely like to subject the press to an unconstitutional censorship regime.

It is not “freedom of the press” when newspapers and others are allowed to say and write whatever they want even if it is completely false!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) 14 de agosto de 2016

In my experience, it goes yet deeper than this. Quietly, privately, political reporters wonder if Trump is a threat to them personally — if he were president, would he use the powers of the office to retaliate against them personally if he didn’t like their coverage of his administration? How certain are they that their taxes are really in order? How sure are they that a surveillance state controlled by Trump would tap their phones and watch their emails for leverage?

I am not saying this drives coverage of Trump, but it recasts negative coverage of him. Trump has made criticism of his campaign a reflection of an ideal journalists are particularly committed to: that the United States should have a free and open press able to scrutinize leading politicians without fear of reprisal. Thus, when Trump bars different publications from his press conference, it becomes proof that they are doing the work that journalists should do, and that a President Trump might make that work impossible to do.

A point in case was Trump barring the Post from his rallies. Rather than endangering the Post’s reputation, it made the Post a symbol of free journalism within the profession. When editor Marty Baron (correctly) said Trump’s action was “nothing less than a repudiation of the role of a free and independent press” and the Post’s coverage of Trump would continue “honorably, honestly, accurately, energetically, and unflinchingly,” every journalist I know cheered him for it.

One of the questions amidst all this is whether Trump will have lasting effects on political coverage — whether Trump has permanently broken the norm of automatic equivalence in political reporting.

“I hate Trump, and I hope he loses,” wrote the conservative commentator Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry. “But I fear one consequence of his candidacy will be an even more biased press in the future.”

I doubt it. Covering Trump this way isn’t freeing. It’s uncomfortable, both for individual journalists and for the broader institutions they serve. I think, if anything, the likely reaction will be overcorrection: The press would be so happy to have a semi-normal Republican candidate it could cover respectfully that whoever follows Trump is likely to benefit from a bit of halo effect just by comparison.

Like so much else in this election, what defines the press’s coverage of Trump isn’t that he’s a Republican, but that there is something abnormal about him, about his campaign, and about the dynamics surrounding it. Assuming more normal politicians succeed him, more normal forms of coverage will reassert themselves.

Read more at: vox.com

Tagged Under: media bias, The Donald, Trump